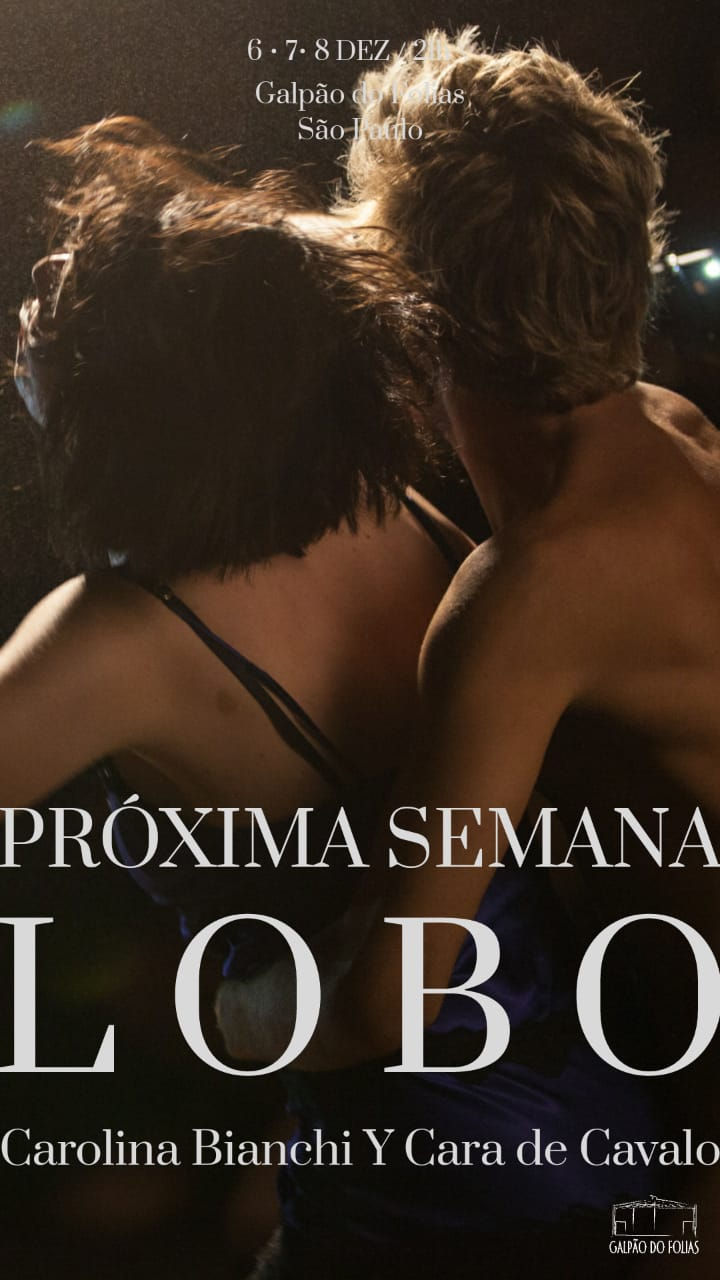

L O B O

Teatro Oficina, 2018

Mayra Azzi

L O B O

"I am my spine and his. His spine that I stick my nails by the front, by the back and I rip out the spine with the force of 700 goats going up the mountains. I rip out his spine with my hands and wave it in the air like a flag. My flag, gentlemen, is the whole extent that connects the cervical to the asshole. My flag have nothing written on it, because if it had it wouldn't be in any language from this world.”

[Carolina Bianchi]

Concepção, direção e dramaturgia: Carolina Bianchi

Performers: Allyson Amaral, Antonio Miano, Blackyva, Carolina Bianchi, Chico Lima, Eduardo Bordinhon, Felipe Marcondes, Gabriel Bodstein,

Giuli Lacorte, Guilherme Conrado, Gustavo Saulle, João Victor Cavalcante, José Artur Campos, Kelner Macedo, Maico Silveira, Murilo Basso, Rafael Limongelli, Rodrigo Andraeolli, Tomás Decina, Tomás de Souza e Wallace Ferreira.

Assistência de direção: Joana Ferraz, Marina Matheus e Debora Rebecchi

Produção: AnaCris Medina e Lu Mugayar

Som: Joana Flor

Luz: Alessandra Domingues

Operação de luz: Lui Seixas

Pesquisa de trilha sonora: Carolina Bianchi

Fotos: Mayra Azzi

Vídeos: Fernanda Vinhas e Aline Belfort

Efeitos: Gustavo Saulle

Objetos de cena: Tomás Decina, Rafael Limongelli e Nelson Feitosa

Figurinos: Antonio Vanfill e Carolina Bianchi

Produção executiva: AnaCris Medina e Lu Mugayar

Distribuição/Produção internacional: Metropolitana Gestão Cultural – Carla Estefan

Direção de produção: Jasmim Produção Cultural

Comunicação: José Artur Campos

CAROLINA BIANCHI shares the stage with 16 more male performers. LOBO happens in a sequence of actions that evoke, through images and mythologies, some relationships between female and male, looking at the historical past of these relationships and asking about possible new pacts between the sexes. LOBO dives into senses such as unbridled passion, sacrifice, death - in an encounter with the imagery of women artists of many times such as Mary Shelley and Artemisia Gentileschi, not to elucidate plots that permeate the relations between sexes until today, but rather, to look at the tragedy of the experiences of affection between the sexes with violence, tenderness and humor.

LOBO is a work that has been adding a lot of people since its debut in 2018 at Teatro de Contêiner in São Paulo. Its team consists of 25 people, in addition to other artists who have already performed in the work in Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre, cities in which the piece was presented after an immersion in A Rebelião de Artemísia [Artemísia’s Rebellion] residence with local artists. It also gathers people in crowded sessions since its premiere in São Paulo, and in short seasons on theaters such as Teatro Oficina (São Paulo), Teatro São Pedro (Porto Alegre), Banco do Brasil Cultural Center and Darcy Ribeiro Film School (Rio de Janeiro).

Resident performers Rio de Janeiro: Aron Moraes, Blackyva, Carlos Bruno, Elias de Castro, Felipe Barros, Filipe Felix, Guilherme Conrado, Hugo Costa, Igor Bahia, Leonardo Bianchi, Lucas Sereda, Maruan Sipert, Venâncio Cruz & Wallace Ferreira.

Porto Alegre resident performers:

“It is only possible to dive in love if there is a space in you to be absolutely vulnerable in face of fire.

I do not dare to think of a life without men. And at the same time I dare to have the desire to cut off their heads and pluck out their intestines as revenge. A revenge that I don't even know where it starts and where it ends. Perhaps on the day that a woman dared to say.

You can't say it without waking up, not one, but two volcanos, you can't say it without leaving 17,000 corpses on the floor.

I love men madly and I say that I would be willing to die for each one of them. I say it to the 16, sometimes 30, performers who accompany me on LOBO.

On the scene we have sex with agony and obsession. All the primordial senses of an existence that contains in the future the eyes of childhood.” [Carolina Bianchi]

I

One day I was in front of a painting called Giaele e Sisera (1620) by the Italian baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi. In the painting she portrays seconds before the murder of general Sisera by the hands of Jael, who will avenge her people against the tyrant general. Jael holds a hammer aloft with her right hand, and with her left hand she supports a stake against Sisara's temple, who sleeps soundly. The woman kills the man while he is sleeping. The woman does not seem to have any remorse in her countenance, only courage. How can we wish men to find that deep rest, in the folds of another man's body, looking at their brothers on Earth so close that love becomes almost unbearable? Revenge is rest after a long run holding broken glass against your chest. It is in rest that there is the anguish of sex. It is in the rest that there is the painless revenge

II

Poetry is the continuation of war by other means.

There are no dead.

All resurrect.

A few years ago I came into contact with the poetry of Emily Dickinson, an American who lived in the 19th century and spent much of her life in her room writing poems that are small enigmas of her obsessive thinking about death, nature, body parts dismembered by love and doubt. “Amherst's Madame de Sade”, as Camille Paglia calls her, has become for me a journey of no return in writing. I wanted to stage works as Emily writes her poetry. Inexplicable, and that contain words that could cut the blade of a sword. For that, there would be no other possibility than to be implicated in what I write, materializing the words through my mouth, this so difficult mouth. To symbolically kill a group of men and resurrect them at the same time. With Emily Dickinson's poetry about truth and beauty, the truth is death. This which is, perhaps, the only truth of human adventure. And beauty, that unbearable purity. “The artist must seek beauty to torture ourselves intimately” says Angelica Liddell. "Everything seems to be an exorcism designed to make our demons flow," writes Artaud.

The poet has no defined sex. Emily is the landscape, a loaded gun. Loving a loaded gun is very difficult.

III

When Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, she immediately showed her manuscript to her husband, Percy Shelley. He got enthusiastic about the story, but said he thought that instead of a monster, the creature Viktor brings to life in an experience of galvanism should be an angel and bring hope to readers. Mary, at this point, after the tremendous grief of losing a daughter in a relationship that included betrayals and distrust of her literary future, asks him how she could write about a perfect creature if there was nothing perfect around her. The abandonment of the creature was the abandonment that the authoress felt in her existence. When Frankenstein perceived himself as a monster, flawed, disfigured, I realized that this point would be a possible interlocution with the work, with L O B O. Dissonant voices from the past. Dead animals, creatures seeking a light, through the ages. And saying the word love, with the same tenderness as a hot spit shared from mouth to mouth.

From the huge and filthy legs of the LOBO [WOLF], I imagined a feast that names our confusion, between men and women. This confusion that animals follow calmly, interacting in the gaps of our language.

Cosé la vita senza l'amore?

[Carolina Bianchi]